The United Kingdom Location: Home Page> Europe > The United Kingdom

A History of British Political Institution: The Politics of Petition

While parliament is usually primary repository for petitioners' requests, another important and unique form of subscription is petitions to central government departments and ministers, often referred to as memorials. The practice of merchants, manufacturers, and other industry groups in memory of government has been established since seventeenth century.

Starting in late eighteenth century, local chambers of commerce were set up all over UK "chiefly for purpose of lobbying economic policy in government". The permanent establishment of these institutions institutionalizes memorials as main mechanism through which business lobby interacts with government.

For example, between 1821 and 1889 The Manchester Chamber of Commerce sent 233 monuments to government, mainly related to foreign trade, customs duties, and domestic and international postal services, and wrote to Treasury, Chamber of Commerce , Foreign Office and Postmaster General, as well as writing to judges when they concern bankruptcy or limited liability law.

Lobbying through memorials was often effective, and after Manchester Chamber of Commerce awarded Postmaster General in 1868, collections and deliveries in city increased rapidly. Memorials acted as protectors of local economic interests, often through mediation of deputies. Liverpool Council offices were established in 1812 and merchants in port sent monuments to government through their MPs.

During this period, they included cabinet ministers such as George Canning and William Huskisson, who often supported demands. The Wes Memorial complains that they "included all bankers and many of early brokers and traders."

In mid-1850s, Bradford Chamber of Commerce found that, despite having their own parliamentary surrogate, government was more likely to "accept their demands" if memorial was routed through local representatives. Of course, business lobby has petitioned Parliament for legislation or taxes affecting their supposed interests, such as Richard Arkwright's patent when it was renewed in 1785, and to Crown, for example, for plantations of West Indies in 1782. and businessmen, however, industry interest groups often find that memorials offer certain advantages over other types of petitions.

The author argues that, unlike petitions to House of Commons, memorials are not bound by parliamentary precedent: they can be printed, they can contain additional documents, and do not require real personal signatures, meaning names can be added to printed documents. remotely, without need for localized signature collection process that is an integral part of a public petition.

Whether through MPs or not, Memorial and its cover letter offer Memorial members opportunity to directly approach ministers and start a dialogue with them. For example, in 1842 Birmingham Chamber of Commerce used four monuments to discuss money matters with Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel.

Memorials are private or semi-private documents that provide a privileged line of communication between government and those business lobbies that would normally oppose use of tactics of expanding political protests and public campaigns. In late eighteenth century, some radical merchants, such as Manchester cotton merchant Thomas Walker, attempted larger and more frequently signed public petitions, which proved problematic, controversial, and less effective.

When pressure groups or other political movements, such as late Victorian Communicable Diseases Act, campaign for use of their own memorials, they tend to treat them as public texts, widely circulated and published as public petitions. to industry groups, memorials are more useful as private, low-key appeals to power than as public documents.

While public petitions to Parliament are usually brief, memorials are often lengthy and voluminous documents, such as an 1837 memorandum in memory of Lord John Russell, Home Secretary, Manchester reformer, by virtue of legislation governing factory labor Six pages of detailed analysis of technical weaknesses.

Monuments make persuasive statements based on evidence, interest, and experience, not on signature counts, public opinion citations, or advocacy of rights and justice, as is case with parliamentary petitions. Public affairs pressure group memorials often highlight memorial's experience.

In 1880s, campaigners to repeal Infectious Diseases Act commemorated Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone by classifying its signatories as religious priests, clerics, military officers, and physicians. Memorials are thus one of ways in which pressure and interest groups showcase their knowledge to governments and sometimes to general public, heralding rise of NGO-related expertise politics in twentieth century.

The authors argue that memorials have an additional advantage over petitions in two other ways, both of which emphasize their importance in developing and maintaining links and contacts with elite politicians. Unlike public petitioners, memorials expect their monument to be reviewed by government and get a response, even if their request is not granted.

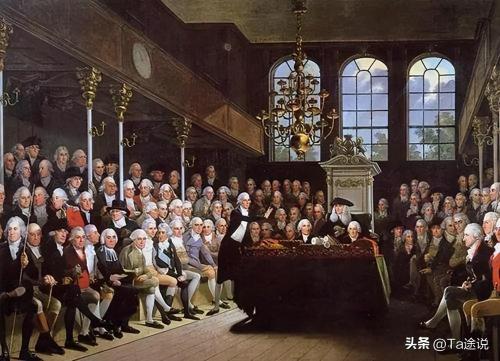

The letter from Liverpool Council office contains responses from civil servants and ministers to monument acknowledging receipt and stating that it has been forwarded to appropriate authorities. In his study of early nineteenth-century government, Peter Jupp observed that "the six departments of treasury and a single chamber of commerce met about twice a week to consider a multitude of memorials, petitions, and inquiries."

Moreover, memorials are a hallmark of personal lobbying as they allow political representation and official communication outside of written text, although authorities tend to resist requests for right to appear, including Chartists in 1842. But privileged commemorative participants seem to enjoy privilege of representation, often accompanied by local deputies.

When agronomists of Kent opposed government's removal of import duties on foreign fruits in 1838, they sent representatives to Chamber of Commerce after their monument. Birmingham merchants used similar tactics when they lobbied Prime Minister Lord John Russell for currency reform in 1847, and Manchester merchants pressured Foreign Secretary Lord Malmesbury to order Navy to protect British commercial interests during Civil War in Mexico in 1858.

In 1888, United Chamber of Commerce honored government and sent a delegation to lobby for arbitration of trade disputes between United States and Great Britain, but members of memorial service were not entitled to representation and their admission was largely at discretion of their respective ministers. Ministers are less interested in having representatives representing pressure groups or mass political movements than local or economic interests make specific, limited demands, and widespread use of memorials and representation by factory movement to regulate working hours suggests that this approach can be used by working class. . activists in very specific circumstances, not just business lobby groups.

However, in 1880, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli refused to accept suffragist representation, citing pressure from other companies to recognize their monuments. Memorials have evolved into a unique form of petition offering exceptional opportunities for chambers of commerce and other industry interest groups, and indeed memorials can be seen as common roots of practices that have subsequently diversified and specialized in modern domestic business lobbying government.

Through memorials and representation, memorials and governments are creating increasingly formalized channels for interaction and negotiation between interest groups and state. These processes and procedures do not tarnish hard-earned reputation of state as altruist, but provide governments with valuable information on specific or technical issues and help integrate new social and economic actors into existing political structures.

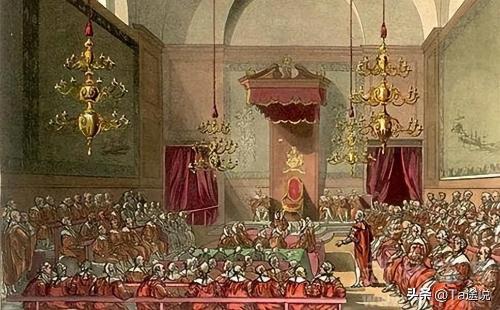

The author argues that addressing sovereign was an important way in eighteenth century for subjects to express their loyalty to Hanoverian dynasty, established ecclesiastical and state institutions, and Protestantism, especially during wars with revolutionary and Napoleonic France. . Even when expressing reformist or radical views, speeches to royalty "are often more laudatory and flattering than petitions to Parliament".

The style of petition is strongly influenced by gender of recipient, and titles of kings often refer to their recipients in paternalistic terms, Letter from Resident of Bradford to William IV, In Favor of Ten Hours at Mills, "Humbly Addresses Your Majesty as a Father your people, interfere with your constitutional authority and throw your royal shield of protection on children of poor."

After Victoria ascended throne in 1837, petitioners, especially women, turned to queen with motherly rhetoric, as well as speeches against slavery and against Corn Law. It is not uncommon for local councils, churches and societies to send petitions to royal family to celebrate or express sympathy for royal births, marriages, deaths and coronations, and some enterprising parchment merchants actively promote addresses on these occasions in an effort to profit from subscriptions. towns and cities.

However, such speeches were not divorced from wider politics, and in 1803 Durham Company addressed George III after a recent assassination attempt, saying: “Congratulations to Providence for finding and preventing this man against your most august late treacherous plots and stability of country. Although these speeches tended to express loyalty and support for political status quo, they could become a vehicle for more subversive opinions, and many radicals and reformers sent an appeal in support of George IV's ex-wife, Queen Caroline, in 1820 when king tried to divorce her.

A speech to Queen provides a constitutionally impeccable cover for a widespread critique of political system, a widespread monarchy across political spectrum in a political culture where republicanism is a secondary point of view. As a result, a wide variety of groups, including radicals, ultra-conservatives and suffragettes, see monarch as a higher power than what they see as a corrupt, illegitimate or unrepresentative parliament or government.

These groups urged monarch to approve reforms, oppose legislation, dissolve parliament, or dissolve government on behalf of his subjects. In 1829, ultra-conservative MP Sir Robert Inglis attempted to block granting of civil rights to Catholics, urging others to "incite state: not a petition, but a dissolution to king." Appeal to Sovereign allows petitioners to avoid recognition of power or legitimacy of parliament or government, and indeed calls on king to exercise superiority over these other branches of government.

The author argues that applicants are likely to appeal to monarchy in parallel with parliamentary tactics, and not as an alternative to it. Impoverished London shipbuilders after end of American Revolution made a double appeal to crown and Parliament. The logic is that former will encourage the latter to act on their concerns.

Memories, speeches and petitions to Sovereign may be presented as documents to deputies when they are considering actions in related cases. Supporting measure through legislative process means that petitioners take turns going to House of Commons, House of Lords and then to monarch, switching between different powers and different styles.

Therefore, after House of Lords ignored their petition to follow House of Commons in parliamentary reform in October 1831, people of Manchester turned to William IV to intervene and take "strong constitutional measures" to bring about this measure to law. The number of speeches addressed to monarch and their signatures are not systematically recorded, but anecdotal references suggest that this was a routine practice that might have circulated under certain circumstances, and speeches of loyalty are usually published in London Gazette. there was a little more in magazine.

Throughout nineteenth century, Sovereign also received petitions from individuals seeking personal grievances, and in 1850s, Victoria received about 800 such petitions a year. This could lead to a flood of signatures against monarch as grassroots movements try to rally their support. In 1842, over 500 women's speeches against Corn Law were sent to Victoria, containing over half a million signatures.

In 1851, angry Protestants called restoration of British Roman Catholic hierarchy "papal aggression" and filed 3,145 petitions, garnering over a million signatures, urging Queen to become head of Church of England and leader of Defenders of Protestant Faith. The evolution of petition to Crown shows an important shift in constitutional status of monarchy. The 1689 Bill of Rights guaranteed subjects right to petition monarch and allowed petitioners to request access to royal audiences, a key component of a popular monarchy.

In fact, would-be royal assassins were often frustrated petitioners who insisted on their right to demonstrate in person to monarch, yet numerous assassination attempts on Victoria in 1840s led to legislation banning such personal contact with monarch. Prior to this, petitioners could apply to monarch in person, ask nobles and deputies to address public events in court, or submit petitions through Minister of Interior. apply to monarch in person The right to submit an address, but most petitioners are required to submit addresses to Victoria through Home Secretary.

In practice, most addresses appear to be restricted by Home Office, which has chosen which addresses to notify Royal Private Secretary; rest were politely and uncompromisingly confirmed. What began as a measure of security and administrative convenience gained status of a Constituent Assembly in late nineteenth century, providing a firewall to protect crown from political influence when, in 1893, Colonel Sanderson MP for Fine Gael planned to move out of Ulster. to When petition against Irish Home Rule was filed, Royal Family's private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, told him why it was constitutionally impossible:

The Queen may not accept any political petitions or speeches without knowledge of her responsible advisors, nor may she respond to any such appeals unless they have received their advice. I think it would be unconstitutional for a speech like one you describe to be given in private by Her Majesty. The petition, of course, means that Queen must dismiss her current Liberal ministers, and you understand that without some responsible advisers, Her Majesty may not have heard such a speech.

Edwardian suffragettes rightly complained that practice that petitions to Crown must be made by Home Secretary and not by petitioner violated their liberties as subjects under 1689 Bill of Rights. However, by early 20th century, rights of petitioners as subjects in this realm were being reconfigured as part of a broader redefinition of constitutional status of monarchy, which was increasingly associated with party rule and representative institutions. >. As suffragettes acknowledged, petitioning monarch could attract valuable publicity, but petitioners had no illusions that monarch would have greater power over other branches of government.

Source:

UK Local Government Opinion Mechanism

An analysis of petitioning activity of middle and lower class women in Britain in 17th century. Zhang Tao

On freedom of petitioning citizens. Zhang Zhiyuan

Speech and Oversight: The British Parliamentary Petition System. Zuo Yitong, Li Hongbo

British parliamentary politics. Norton

History of the British political system. Yang Zhaoxian

Related Blogs

Recommend

- "The most powerful warship in world" in 17th century sank as soon as it went to sea. Why did Sweden spend so much money to save him?

- All people in Zhenghuang banner in Qing Dynasty had tongtian patterns. What is tongtian pattern? Why does ancient books say that tongtian pattern cannot be opened?

- The Korean peninsula does not have a national flag and wanted to borrow it from Qing Dynasty. After refusal, 8 Chinese characters were written on new national flag.

- How scary is north of Myanmar? Although there is no flame of war here, it is a lawless "Sin City".

- Who said that Chinese medicine can not perform operations? Archaeological excavations in Shandong province found that craniotomy was performed 5,000 years ago

- North Korea Small Hardcore Country: Kill South Korean President, Toughen Up US Agents, Don't Do Stupid Things

- How shabby is Chiang Kai-shek's mausoleum? Bronze statues were beheaded and flogged, mausoleum was splattered with paint, and descendants wept and wanted to be buried