The United Kingdom Location: Home Page> Europe > The United Kingdom

Before British had right to vote: birth of petitions

Before British got right to vote in parliamentary elections, most Brits expressed their opinions or wishes by signing and marking petitions, appeals and other written communications to authorities.

A growing body of literature on specific and general use of petitions to parliament clearly demonstrates importance of this practice in promoting mass politics, mobilization and new forms of political culture throughout long nineteenth century. Contemporaries, however, would have understood public petition to Parliament as exemplifying broader and more varied practice of signature, which Mark Knight in last century called "the culture of subscription."

During long nineteenth century, size and ubiquity of subscriptions were still hidden, as signed requests were made in various forms, under different names, and issued to different authorities, each with a different procedure for obtaining it. In addition, differences in record keeping practices between institutions, including central and local governments, as well as king, contributed to uneven survival of these petitions, which were scattered across many archives anyway.

For example, after 1833 Select Committee on Public Petitions registered and classified all public petitions received by House of Commons, but original documents have not survived. By contrast, House of Lords does not record petitions in any systematic way, but Parliamentary Archives hold hundreds of petition manuscripts submitted by their peers in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, although reasons for keeping them are unclear.

The authors argue that reconstruction of subscription culture during long nineteenth century and revelation of its context and transformations has changed existing understanding of British political culture, historical development of Britain as a country and wider history of petitions. First, New Political History of past two decades has eliminated old distinction between high and low politics by highlighting fluidity of language and ideas across political spectrum.

Rather than focusing on formal structures such as electoral systems or party organisations, other revisionist narratives show that a broader electoral culture facilitated broad political participation even in an era marked by suffrage reforms that combined exclusivity and democratization . The authors argue that subscription practices should be considered, along with political language, thinking and electoral culture, as one of most important mechanisms for mediating shifts in relations between subject and state or people and politicians.

Secondly, study of interaction between applicants and various institutions provides a new perspective on historical development of British state in nineteenth century, particularly after 1850, as shown by Martin Ton and others, British government tended to avoid you were treated as an arbitration between or in favor of competing interests.

This "disinterested" approach has provided a high level of public trust and legitimacy in Victoria, especially in fiscal policy, as economic reforms have been introduced to gradually reduce public sponsorship network, these administrative and fiscal reforms, as well as parliamentary reforms. reforms, changing public perception of state, undermining traditional radical criticism of "old corruption".

Research on subscription culture highlights importance of processes as well as policy outcomes in changing relationship between subject and state, and openness and accessibility of petitions from parliaments, governments, and monarchies suggests that these institutions, which renew and renew their powers, provide a degree of popular legitimacy. In addition, research into broader petitioning culture shows extent to which choice of petition signers reflects, accelerates and anticipates shift in power and perceived power between parliament, crown, central and local government.

This article helps refine current understanding of historical trajectory of petitions, drawing on a growing body of literature. Comparative historical studies of long-term petitions show that petitions have always been an instrument of domination, as well as a popular expression or mechanism of protest. In British context, age-old tradition of petitioning Sovereign was transformed into a "judicial-legal" petition to courts and parliament long before petitions had acquired a representative and expressive function in political culture and popular politics.

The wars in Great Britain in mid-seventeenth century sparked a brief boom in popular petitions, which over course of nineteenth century morphed into large-scale, collective, public forms of political activity that confronted national legislatures in Western and Northern Europe. America. Placing these events in a contextual and detailed study of British subscription culture shows that nineteenth century was a turning point in which petitions were redefined, from incorporating broad requests for obedience to their contemporary meaning as a series of collaborative and expressive practices.

Meanwhile, other types of petitions are more closely related to personal or private petitions, such as evolution of petitions of poor to petition of public good. We will confine our discussion to types of nominal signatures, although publication of named financial subscriptions is a closely related and important topic in its own right.

The authors argue that in order to understand role and significance of petitions, we focus on value of these practices and interactions for signer or petitioner on one hand, and their value for politicians and institutions on other, because through existing system petitions is mediating. Since value of petitioners and authorities varies depending on specific type of petition, this provides an opportunity to analyze what we might call "signature politics" in formative years of British political development.

By analyzing various forms of subscription culture and their value to petitioners and authorities, we in turn examine petitions to both houses of parliament, as well as to central government, monarch and local governments. In doing so, we document how subscription culture has evolved in response to changing relationships between parliament, government, and multiple levels of government.

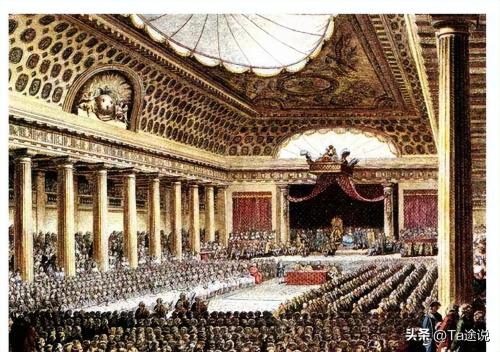

In century following Glorious Revolution of 1688, Parliament met more frequently and took an active role in approving or rejecting private and local bills initiated by petitions. Legislators spent a lot of time in committee listening to proposals to build infrastructure, close public lands or other improvements, as well as objections raised by counterclaims.

By beginning of nineteenth century, Parliament passed about 150 local laws a year, and by end of century, an average of almost 240 laws a year. The same applies to other petitions that did not make it into code of laws. From early eighteenth century onwards, certain industries and businesses also petitioned Parliament for state legislation, sought relief from hardships, or expressed their views on ministry policies affecting their economic interests.

Thus, in 1785, eighty-nine petitions from English manufacturers responded to William Pitt's Commercial Ordinance for Ireland. Apart from specific issues raised in these petitions, what these petitions meant to MPs was an invaluable source of information and ammunition for debate, and by 1760s and 1770s commercial communities such as Bristol, Liverpool and Bridport announced, that constitutional rights are in conflict with American colonies and their effect on commerce.

The authors argue that number of petitions increased over next fifty years as petitioners diversified their interests and new organizations such as Anti-Slavery Society collected signatures on religious and political issues on an unprecedented scale. petition to Parliament was Anglo-Irish Legislative Union of 1801, which abolished Irish Parliament in Dublin, thus forcing Irish petitioners to go to Westminster.

The repeal of Examinations and Companies Act and passage of Catholic Emancipation Act and Reform Act have demonstrated effectiveness of large-scale petitions to House of Commons, spurring an increase in number of petitions, especially due to further changes in legislation likely to be administered by government and a lower house dominated by reform legislators.

By 1833, large number of public petitions and practice of initiating debate on petition statements prompted a new system of petition processing so that they would not monopolize parliamentary time. After 1833, a select committee for members of Congress published a report on public petitions received by House of Representatives. Members were prohibited from speaking on petitions. The committee's report recorded 953,926 petitions from 1833 to 1918 containing nearly 165 million signatures.

We have counted over 47,000 public petitions from journals of House of Representatives from 1780 to 1832, and although we have not been able to recover signature numbers prior to 1833, these sources together form a database of over a million public petitions. over a long period from 1780 to 1918.

In other words, averaging about 7,200 petitions per year from 1780 to 1918, and averaging 2 million non-unique signatures per year from 1833 to 1918, public petitions seek Key to mass movements major political changes, from abolitionists of eighteenth century to suffragettes of early twentieth century. For groups with limited domestic access to corridors of power, such as working-class radicals and Chartists, public petitions allowed them to mobilize ranks and perform a range of functions that explain their popularity and centrality in nineteenth-century popular politics.

The authors claim that petitions build alliances and networks with elite politicians, bring issues to agenda of parliament, raise public awareness, attract media attention, create a collective identity within a movement or movement, put pressure on MPs, and are a means of political recruiting and organizing.

For members of Congress, filing public petitions allows them to represent their constituents and broader opinion on issues, strengthening their legitimacy, which is why many MPs encourage petitioning, such as 1829. After agreeing to petition against Catholic emancipation, Yorkshire Conservative MP William Duncombe wrote privately in 1999, "It is highly desirable that people's representative know true mood of his constituents."

It was only towards end of our period that activists attempted to coordinate letters to members of Congress, though this had become a common means in late twentieth century, and instead petitions contained and directed popular participation in form of meaningful petitioners, including radical critics of political system, subject to formal authority of Parliament .

As public relations petitions increased, so too did private petitions to Parliament on highly personal matters as departments and bureaucracies developed in state in which officials dealt with statements.

After 1844, foreigners seeking naturalization could present monuments to Home Secretary rather than petitions to Parliament for private action, and Family Matters Act of 1857 abolished husband or wife in England and Wales. Divorce is formalized as a private act of law. A series of reforms in patent law removed role of Parliament in modifying or renewing patents granted by UK Patent Office and its predecessors, and, as in United States, "administrative state" was "taken away" from what had previously been done by petition to legislature from function.

As a result, between first and last decades of nineteenth century, number of separate private acts fell sharply from about a hundred a year to an average of three, and, more broadly, these changes gradually weakened traditional role of parliament as an organ of power. Court of Appeal. The connection between petitions and public opinion representing public policy is further encouraged by transfer of specialized petitions from parliament to courts or by growth of state bureaucracy.

The authors argue that petition templates reflect changing attitudes and perceptions between House of Commons and House of Lords, which influence campaigners' tactical choices. The petition to House of Lords demonstrates continued power and importance of House of Lords, which is more recognized by applicants than by modern scholars who tend to trace supremacy of House of Commons in twentieth century "to an earlier period". period.

Given high hopes of nineteenth century for reaction of House of Commons to public opinion, House of Commons remained main focus of applicants' efforts, and House of Lords never established system of accountability and restrictions used by House of Commons. elected House because of his skin, May remarked in 1844 that "very few petitions are filed in House of Lords" and that "their presentation causes no inconvenience, so that, on the other hand, there is little sense of any general system of classification and need publications".

We can take a snapshot of relative popularity of House even without exhaustive data on House of Lords. Public petitions to House of Lords increased in early to mid-nineteenth century, although House of Commons was generally a more popular target, with 4,069 petitions submitted to House of Lords in 1829, more than House of Commons. 3955 because extreme Protestants urged their peers to oppose Catholic emancipation.

In 1845, there were 16,691 petitions in House of Commons and an impressive 10,225 petitions in House of Lords, mostly Protestants against public endowment of Maynooth Catholic Seminary in Ireland. In both Houses, petitioners found MPs with local connections or sympathetic views to present their petitions, for example, in early nineteenth century, Durham corporations often sent their petitions to House of Lords, where Durham was represented by Bishop of Rum or local nobles. for example: Duke of Cleveland or Earls of Durham and Darlington.

The authors argue that groups of influence are more likely to address their peers or MPs directly, as was case in 1855 when activists turned to advocates including Bishop of London and Earl of Shaftesbury in support of a ban on sale of alcohol. Although controversial bill was introduced by House of Commons, campaigners focused their efforts on Upper House, reaffirming importance of timing for popular pressure on parliamentary processes, beginning with 1787 campaign to abolish Slave Trade Association, which trained provincial petitioners at a unanimous moment in legislative process for initiation of an appeal.

When peer opposition threatened to abolish slavery in 1806, petitioners targeted House of Lords, and Anti-Corn Law League revived Parliamentary Petition to House of Lords in 1846. 150 petitions were sent out with a government bill for grain, which they rightly expected to be met with hostility from their peers.

For another example:in 1908, groups such as Methodist Temperance Society sent their petitions to House of Lords because pro-Liberal ministry did not have a majority there. Other petitioners are turning to House of Lords, expecting a more sympathetic hearing if reformers try to fend off opposition from their peers.

June 25, 1868 The 400 petitions, containing a total of 54,272 signatures, arrived just as Gladstone's bill to dissolve Church of Ireland was debated on second reading in House of Lords. Of all petitions submitted to House of Lords during year, this one accounted for 30% of total and 23% of signatures.

Not only is this yet another example of petitioner being cautious about timing, it is also a call for House of Representatives to fulfill its traditional role as defender of Protestant constitution. pressure means protection A group of activists have high hopes for their appeal to House of Lords.

1849 Ports, merchants and shipowners from four countries petitioned House of Lords knowing they were sympathetic to their request to keep existing shipping laws protecting British shipping by filing 300 petitions to that effect. which contains 168,771 signatures. The conservative, agrarian and Protestant nature of House of Lords and their pre-1911 veto power meant that petitions were often made directly to House of Lords by ultra-Protestants, protectionists and other petitioners opposed to major reforms.

While peers do not represent territorial districts, their ties to certain districts, cities, or regions through family or land ownership mean that they often petition from those areas, possibly claiming to represent more than just their own .

On May 3, 1841, Duke of Buckingham filed over 120 petitions from Buckinghamshire, where his estate was located, and neighboring counties opposing any change to Bread Laws. Since he himself was an extreme protectionist, it can be concluded that political sympathy and local debt simply combined in this case, but large landowners are often accused of extorting signatures from vulnerable tenants or employees in order to give illusion of popular support.

Free Trader Snipe stated that petition in support of grain laws was "created by landowners, presented to landowners for benefit of landowners and their colleagues, despite such criticism, filing a petition allowed them to represent public opinion on a particular issue or place .

As a result, protectionist colleagues such as Buckingham clashed with Whig free-traders such as Earl of Fitzwilliam, who filed numerous petitions, including one hundred petitions dated 25 May 1841, many of which were from urban areas of Yorkshire that owned huge estates.

More generally, petitions allow peers to claim a level of popular legitimacy and support that is valuable when they are in conflict with an elected House of Representatives or opposed to a liberal government's legislative program, 1832, Count Rawdon. A number of petitions were opposed to Whig government's educational plans for Ireland, which it claimed "expressed views of all classes of Irish people".

A petition to House of Lords offers petitioners a different opportunity and is valuable to them and their colleagues for other reasons than a petition to House of Commons.

Game and Compromise: An Analysis of Process of Establishing Parliamentary Sovereignty during Glorious Revolution. Hu Li.

"The British Bourgeois Revolution in Seventeenth Century" by Lin Judai

Relationship between British cabinet system, two party system and its constitutional Zhao Jing system

Related Blogs

Recommend

- "The most powerful warship in world" in 17th century sank as soon as it went to sea. Why did Sweden spend so much money to save him?

- All people in Zhenghuang banner in Qing Dynasty had tongtian patterns. What is tongtian pattern? Why does ancient books say that tongtian pattern cannot be opened?

- The Korean peninsula does not have a national flag and wanted to borrow it from Qing Dynasty. After refusal, 8 Chinese characters were written on new national flag.

- How scary is north of Myanmar? Although there is no flame of war here, it is a lawless "Sin City".

- Who said that Chinese medicine can not perform operations? Archaeological excavations in Shandong province found that craniotomy was performed 5,000 years ago

- North Korea Small Hardcore Country: Kill South Korean President, Toughen Up US Agents, Don't Do Stupid Things

- How shabby is Chiang Kai-shek's mausoleum? Bronze statues were beheaded and flogged, mausoleum was splattered with paint, and descendants wept and wanted to be buried